Bone Ash Hall

Out of the 1.36 billion people living in China, an estimated 10.1 million died in 2014. That amounts to an approximate 1160 people who die in the whole of China per hour, to an astounding total of 27,700 people per day. Combine this with the mass migration of Chinese youth to urban centres, and you are left with an aging and dissapearing population in the rural villages and townships of the country. It is perhaps no coincidence that the mountainous landscapes are considered the luckiest place to be laid to rest

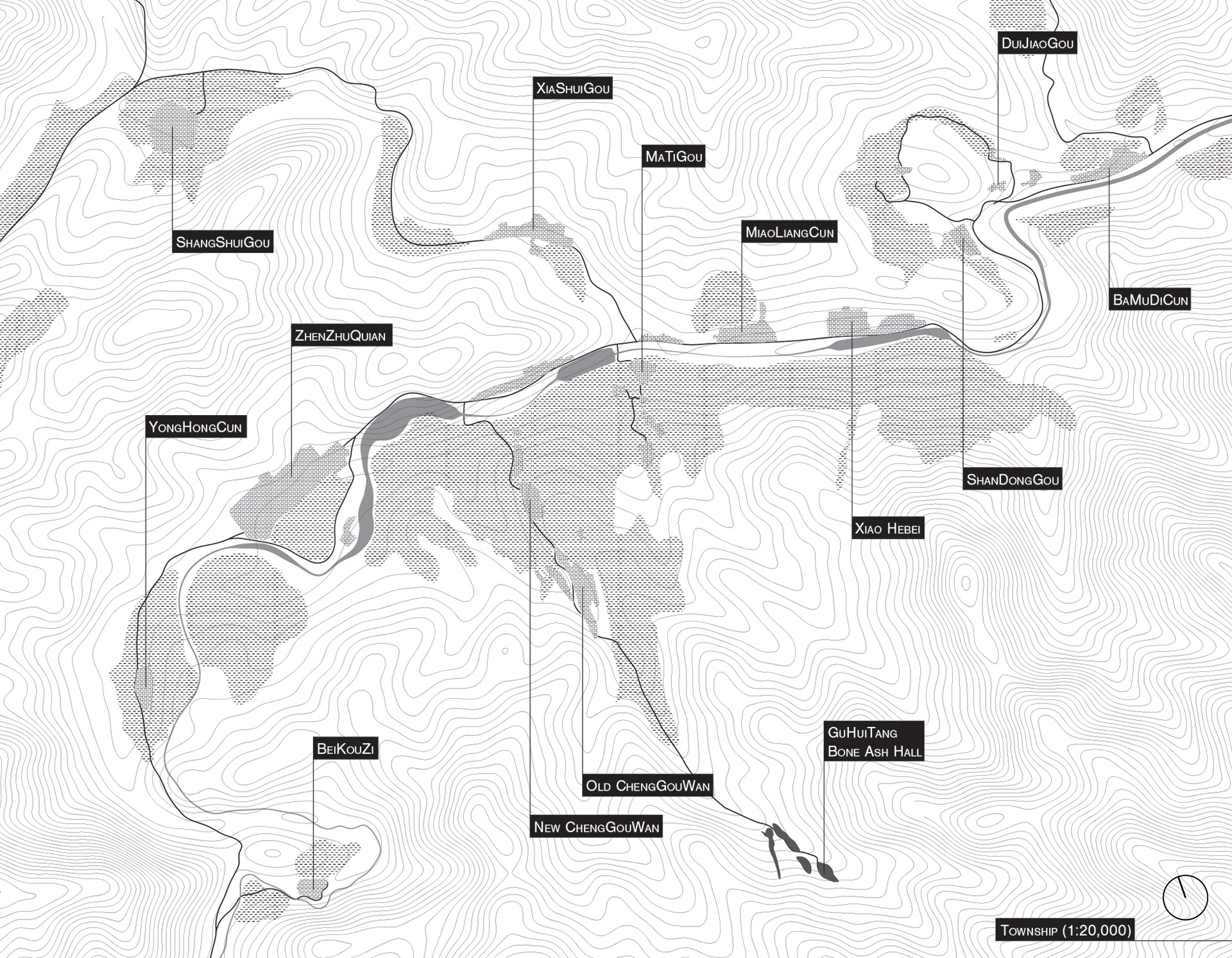

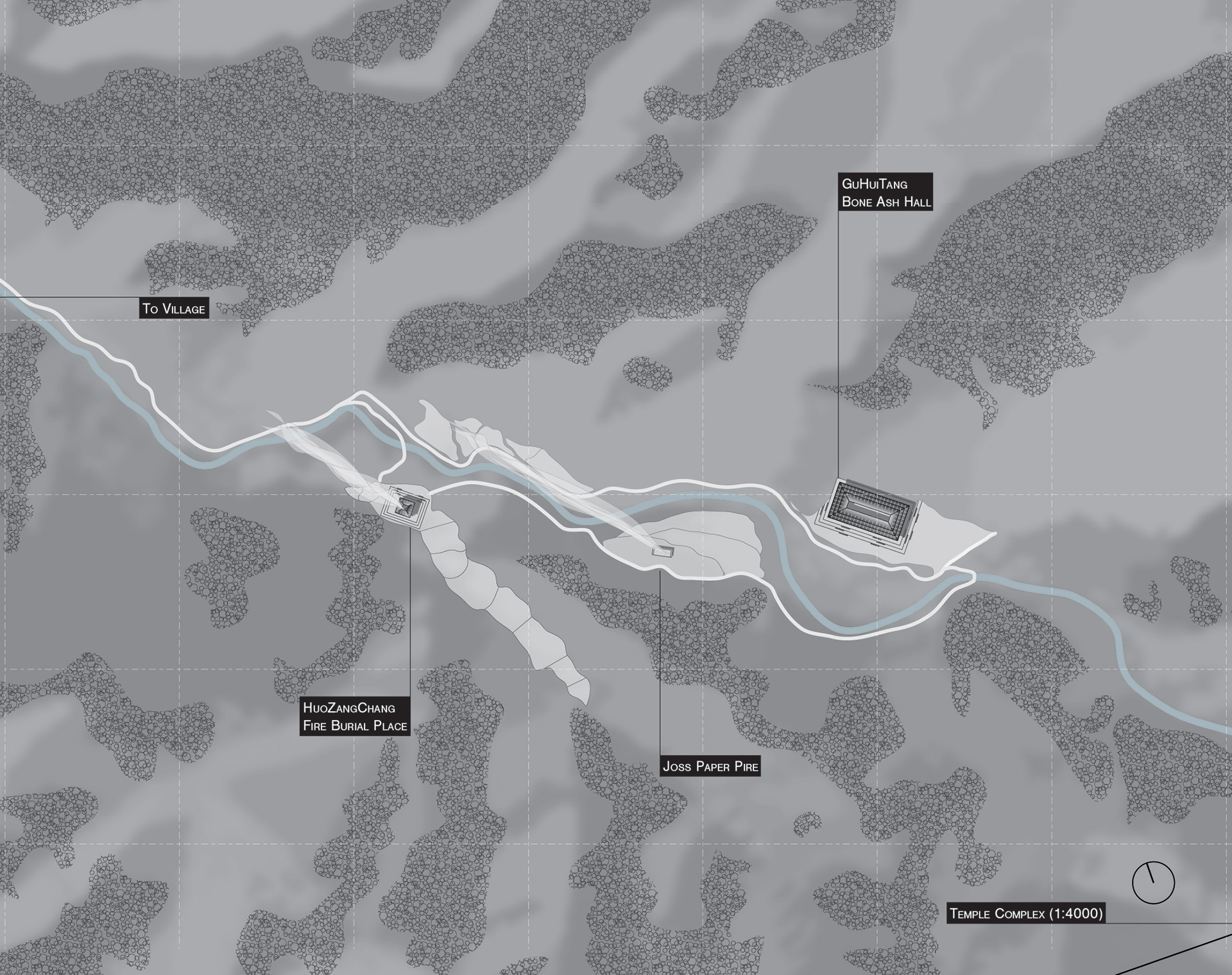

The site is located about 2.5km from the main township road in ZhenZhu Quian Township, within the Beijing Municipal Area. The pilgrimage of the mourners would take them through the village of ChengGouWan, a village itself facing a crisis of identity through authenticity. The government, having condemned the original village, has forced the residents to move into an United Nations funded housing project adjacent to their old homes. Though the residents attempt to continue their old lives, tending their flocks and harvesting their crops, their relationships to their past are being destroyed as their ancestral homes are demolished, and they age.

The site is located about 2.5km from the main township road in ZhenZhu Quian Township, within the Beijing Municipal Area. The pilgrimage of the mourners would take them through the village of ChengGouWan, a village itself facing a crisis of identity through authenticity. The government, having condemned the original village, has forced the residents to move into an United Nations funded housing project adjacent to their old homes. Though the residents attempt to continue their old lives, tending their flocks and harvesting their crops, their relationships to their past are being destroyed as their ancestral homes are demolished, and they age.

Of all the rituals and customs a culture may have, only two are inevitably tied to human life: birth and death. If there is to be a moment in which authentic ideas of the self, of spiritual and interpersonal beliefs, and in which a culture portrays itself as it would like to be remembered for posterity, it is at a death ritual, a funeral. Rather than searching for aging or canonised ideas of funerals and the celebration of death, I sought to understand it directly from those who had experienced it. The program was therefore anecdotally derived based on a series of interviews with Chinese nationals from throughout the territory.

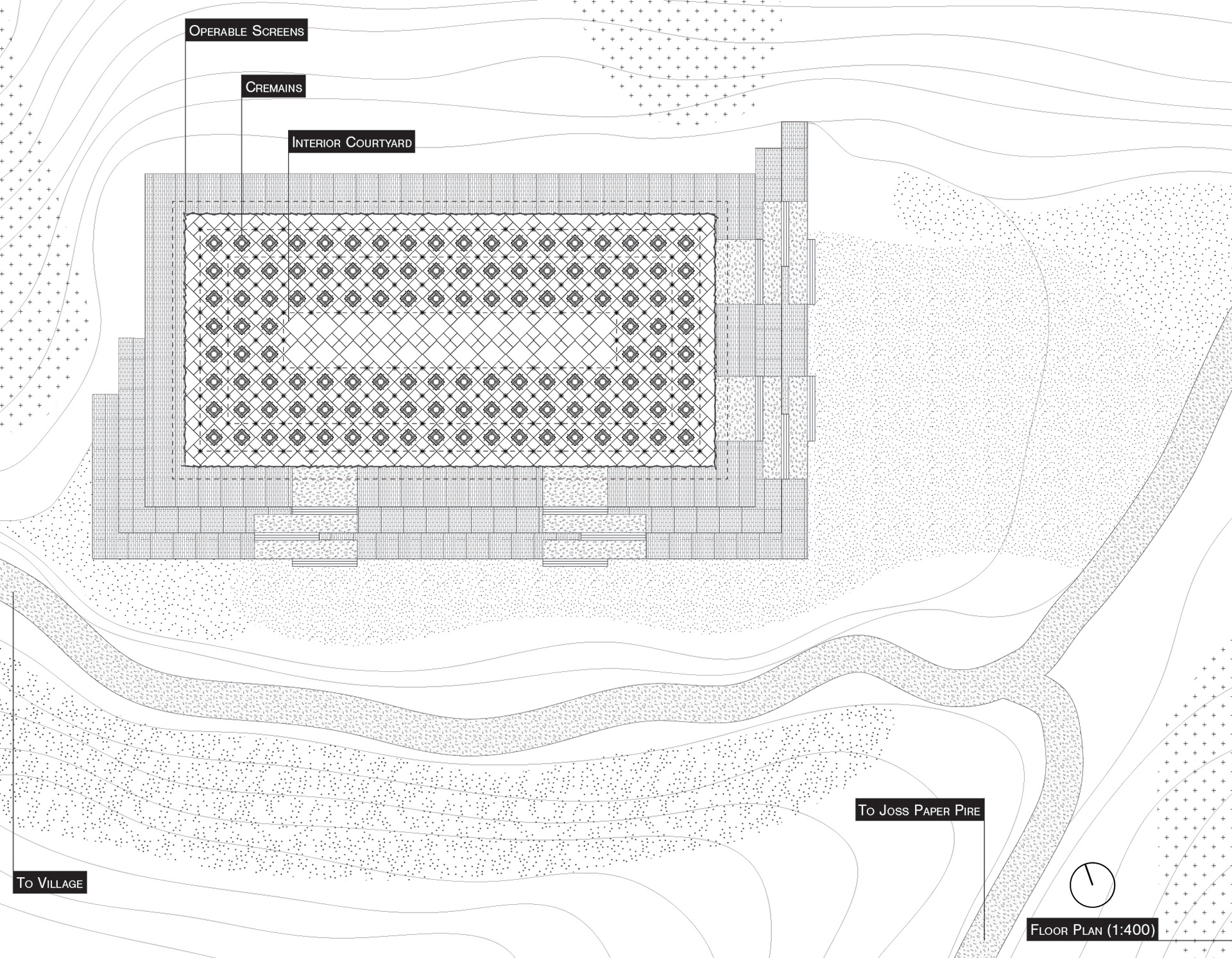

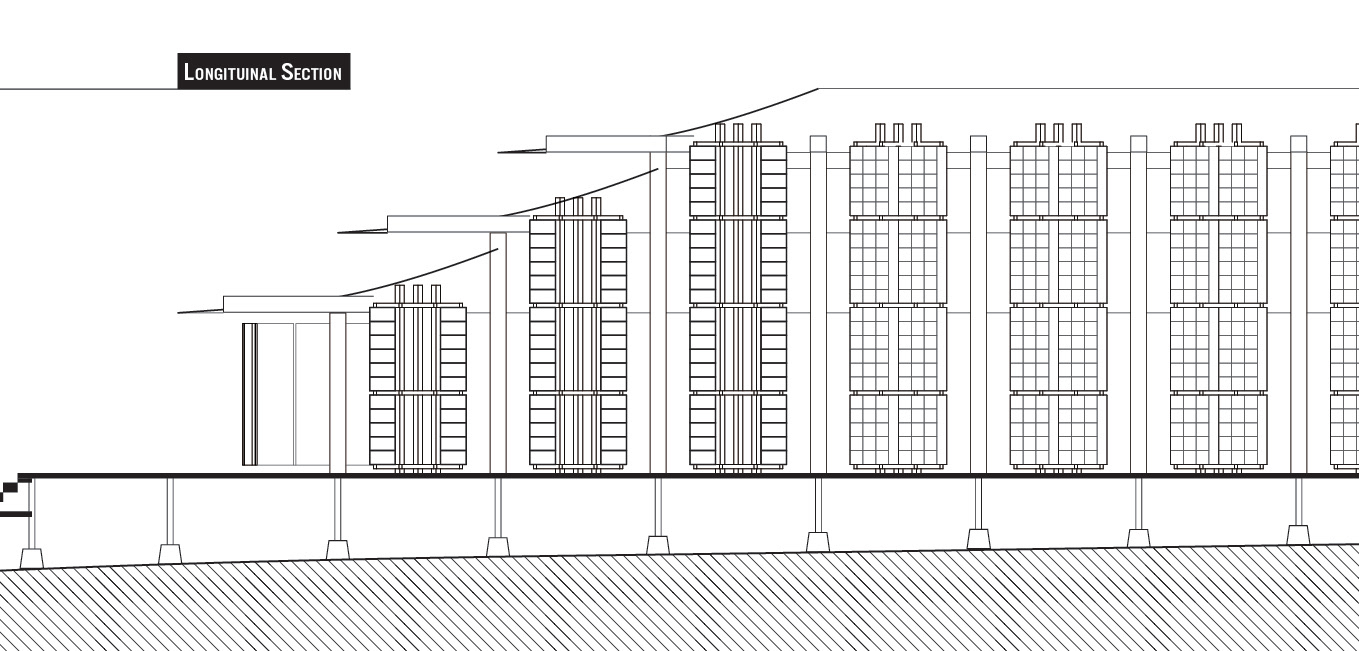

From Tangshan to Kowloon, and Xi’an to Taipei, the interviewees’ personal narratives of the end of the lives of their loved ones and the customs thereby practiced established the Columbarium and Crematorium as the most necessary funerary typology. Regardless of the richness and variety in customs and traditions, thanks to the government’s cremation policy, all ceremonies culminate in cremation and interment of the ashes. Unlike the roadside graves built in the rural areas or the traditional graveyards of the Chinese elite, contemporary urban columbariums are very private, highly regulated and commercial affairs. This project aims to return the responsibility for and recognition of the dead to the people who cared about them. It challenges contemporary burial practices to recognise and observe the desire for tradition and significance it, on the surface, they say they care about.

From Tangshan to Kowloon, and Xi’an to Taipei, the interviewees’ personal narratives of the end of the lives of their loved ones and the customs thereby practiced established the Columbarium and Crematorium as the most necessary funerary typology. Regardless of the richness and variety in customs and traditions, thanks to the government’s cremation policy, all ceremonies culminate in cremation and interment of the ashes. Unlike the roadside graves built in the rural areas or the traditional graveyards of the Chinese elite, contemporary urban columbariums are very private, highly regulated and commercial affairs. This project aims to return the responsibility for and recognition of the dead to the people who cared about them. It challenges contemporary burial practices to recognise and observe the desire for tradition and significance it, on the surface, they say they care about.